British abolitionist painting goes on display for the first time

A painting that was made during the early phase of the British movement to abolish transatlantic slavery has gone on public display for the first time at the International Slavery Museum, Liverpool.

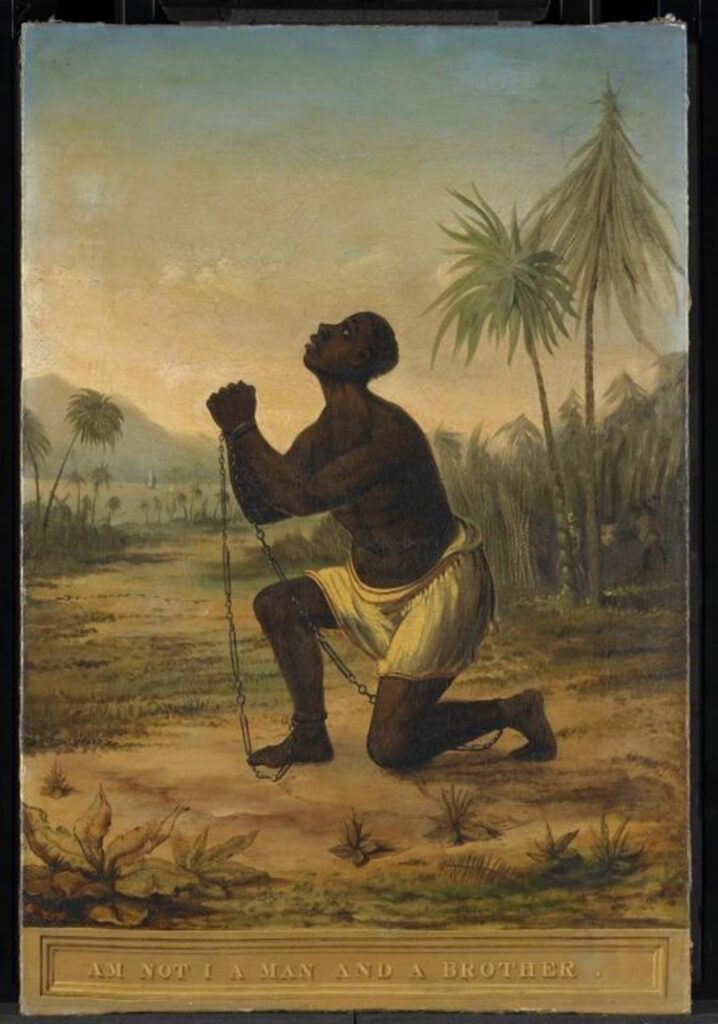

Am Not I A Man And A Brother, painted around 1800, depicts an enslaved African, set against the backdrop of a Caribbean sugar plantation. The motif of the kneeling enslaved man originated from the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade and the Wedgwood medallion. As the movement gained support, this iconography would appear on men’s snuff boxes, ladies’ bracelets, hair pins, as well as household objects such as milk jugs and sugar bowls. Am Not I A Man And A Brother is one of only two paintings known to feature this image.

The painting was acquired in 2018, thanks to funding from the Art Fund and the Heritage Lottery Fund’s Collecting Cultures programme. Since then, it has undergone sensitive conservation work to prepare it for public display. It is the first in a series of display changes at the Museum, which will ask visitors to consider how we understand these objects today.

Am Not I A Man And A Brother has been deliberately positioned next to another powerful painting, The Hunted Slaves by Richard Ansdell. Painted in 1861, this painting may be seen as a powerful indictment of slavery in the United States at that time. It shows two enslaved people who have escaped, only to be hunted down by a pack of savage dogs.

The two paintings present contrasting depictions of enslaved people, and the new display encourages visitors to reflect on the impact of seeing these paintings side by side. Am Not I A Man And A Brother depicts a historical representation of enslaved people that feeds the misconception that enslaved people were passive acceptors of their fate.

In fact, the opposite was true as enslaved Africans were the main instigators in their fight for freedom. In contrast, The Hunted Slaves shows an enslaved man with a weapon raised in his fist, poised to fight back against the dogs that bear their teeth in attack.

Madelyn Walsh, Project Assistant Curator at International Slavery Museum, said: “This display represents an important change to the ways in which we exhibit and interrogate objects here at the Museum. It highlights how our understanding of history can change when we alter the perspective, and the importance of critiquing misconceptions that frequently emerge in relation to transatlantic slavery.”

The Museum will ask questions to visitors in the hope of reframing how the objects in its galleries are perceived in today’s world. This collaborative approach to the sharing of knowledge, stories and ideas is known as ‘call and response’. In African diasporic culture, this method of a speaker calling to elicit a response from a listener is a common mode of communication or performance.

In a nearby case on the gallery, five objects have been selected by members of the curatorial team, reflecting their current research. They ask visitors to respond to the question, “How do we understand these objects today?” Although little is known about the objects, the curatorial team feel that they have important stories to tell, which could be revealed by opening up conversations with Museum visitors.

The objects are: a feather headdress donated by Anti-Slavery International; a tambourine made from a ledger of enslaved people; a splinter from the Morant Bay Rebellion; postcards showing historical re-enactments from the 1907 Liverpool Pageant; and West Indian Bangles.

Visitors can share their thoughts on the objects on a nearby response wall, with the responses helping to inform the redevelopment of the Museum. These display changes invite visitors to collaborate with the Museum’s curatorial team as they begin reinterpreting the collection as part of the Waterfront Transformation Project.

The International Slavery Museum will be transformed from a single floor gallery space into a prominent museum, with its own front door via the Dr Martin Luther King Jr building. Creating new and much-needed exhibition spaces, with places for people to connect, reflect and celebrate, the project will set the foundation for the integration of Black heritage across all of National Museums Liverpool’s venues.